The intro of the restoration informs us that the original length of the film was 1705 meters - over 200 meters longer. That may partly explain the vagueness of the plot.

It is also possible that the film assumes its audience is already familiar with the popular novel that it adapts (although some critics felt the novel itself was poorly constructed and confusing). So for those of us that prefer to spend our time watching movies rather than reading 500-page 19th-century novels, here is a cheat sheet that provides relevant plot details from the the English translation of the novel.

Marina arrives at the castle

Immediately on arrival, there is a striking contrast between the free-spirited ways of young Marina and the somber demeanor of her uncle.

Immediately on arrival, there is a striking contrast between the free-spirited ways of young Marina and the somber demeanor of her uncle.

But the Count was Marina's nearest relation, and, of all the family, he alone offered her a home. Marina would have refused the offer if she could have done so. The appearance, habits, and stern speech of her uncle roused her dislike...Only, she had not an independent fortune; so she accepted the Count's offer. She accepted it coldly without a word of gratitude, as though Count Caesar, her mother's brother, did but fulfill a duty, and in so doing obtained the advantage of a companion in his dreary solitude. Not that she was afraid of the prospect of living there; on the contrary, she rather liked the idea of the castle buried among the mountains, where she would dwell like a banished queen who prepares, in the shade and silence of the forest, to regain her throne. The danger of being buried alive forever did not even occur to her, for she had a blind and complete faith in fate; and, feeling that she had been born to enjoy the splendours of life, she was disposed to wait her return to them in haughty indolence.

From this passage it is clear that Marina is free to leave the castle. Although the introduction of the 1942 film version states:

"The uncle, a man of severe principles, imposes one condition: Marina will leave the palace only when married.",

this is an embellishment. It contradicts the dialogue below that occurs when the Count angrily hints that Marina should consider marriage to her cousin as a way of leaving and tells her, "...we cannot go on living together indefinitely...", to which she replies:

' Thanks. And if I don't take a fancy to his lordship when am I to leave ? '

‘But,' said he, 'when am I to leave?' It appears to me that it is you who, by your conduct, display a desire to go away. It would, perhaps, be more honest and straightforward if you were to say, When can I go ? '

'No, for I can go when I please. I am of age, and my means are sufficient to maintain me and an old lady-companion, who will leave me to myself. When am I to leave ? I have no desire to go away.'

' You do not wish to go away ? Then you wish that I should, eh? That would suit your views? But, in Heaven's name, speak out. If you do not wish to go away, what on earth do you wish ? Why do you comport yourself towards me as though I were your gaoler?

What harm have I done you ? '

The fearsome legend

When Marina rejects the room prepared for her, the Count assigns her to "Cecilia's room". This horrifies a servant, who informs Marina that "it's a cursed place" where Lady Cecilia, the first wife of the Count's father, died as a prisoner.

While the servant's concerns are met with laughter from Marina, her face reveals that the story has touched something inside her.

While the servant's concerns are met with laughter from Marina, her face reveals that the story has touched something inside her.

Even her stern uncle was at last won over by Marina...At first, Marina's impetuous bearing puzzled him and roused his distrust ; and her strange behaviour on the stormy evening when she arrived was to him an inexplicable enigma. He then offered her a more cheerful room in the left wing of the castle, but Marina refused it; she liked the fearsome legend narrated to her by Giovanna.

Every kind of plant, and with more poisonous than health-giving

The novel includes lengthy descriptions of Marina's literary tastes:

...her books, a collection, be it said, of every kind of plant, and with more poisonous than health-giving specimens among them.

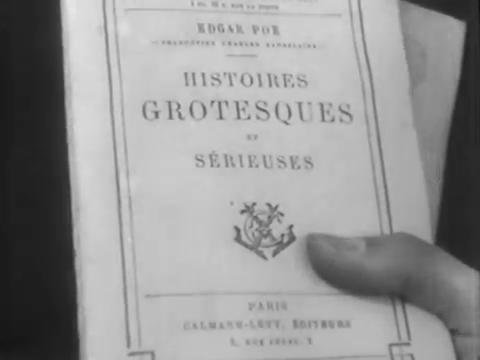

English authors were represented by Shakespeare and Byron...by Poe...She had all George Sand's novels...Baudelaire's Fleur du Mal...She had made her selection in a spirit of research, paying little heed to obvious dangers.

The title of Baudelaire's translation of Edgar Allan Poe makes it clear that Marina was not timid in her reading.

The title of Baudelaire's translation of Edgar Allan Poe makes it clear that Marina was not timid in her reading.

The novel also devotes a page and a half to Marina's disdain for Steinegge, the Count's secretary.

...On Marina's arrival the poor man had considered it his duty to ply her with attentions and endeavour to amuse her...He laid himself out to bombard her with stately compliments and antiquated gallantries...His efforts were not crowned with any brilliant success. The only notice which Marina deigned to take of the secretary was to indicate by a glance, or an ironical remark, how lightly she esteemed his politeness, his attempts at wit, his aged and dried-up person.

In replying to the Count's frustration in the dialogue quoted above, she hilariously sums up her view of Steinegge:

'... Why do you comport yourself towards me as though I were your gaoler? What harm have I done you ? '

'You ? Nothing.'

'Who then ? Steinegge ? What has Steinegge done ? '

'He has frightened me '

'How do you mean frightened you ? '

'He is so ugly.'

This scene (together with the intertitle that precedes it) is a clever embellishment, only in the film, that succinctly captures Marina's intellectual and aesthetic distance from her surroundings, as well as her attitude toward Steinegge, the Count's secretary - in a defiant proto-Mae-West style that needed no words. Listen closely and you can hear Steinegge's testicles drop through the floor.

As though the desires of the ghostly sinners had entered into her

Up to this point, the film has made no reference to the passage of time - which only adds to the obscurity of the plot. But now an intertitle reveals:

April came, carrying flowers, feasts...and a great misfortune for Lady Marina.

But since the month or season of Marina's arrival was not given, this is not much help.

Here, the novel provides a more explicit chronology (while also providing a basis for what is about to occur):

She had passed a year at the castle, and there was as yet no talk of any change. Her health began to suffer in consequence. Nervous attacks, not serious indeed, but of frequent occurrence, began to make themselves felt. She determined to make these serve her purpose; in the meanwhile, any distraction was welcome, even such as she derived from Rico's chatter.

Thus April of 1863 arrived, and with it, in the calm splendours of the sunset, an evening of ill-omen to Marina.

Sullenly glares directly at the audience: a look of someone powerful, yet at the same time helpless.

Sullenly glares directly at the audience: a look of someone powerful, yet at the same time helpless.

Much like the look of Nana, Anna Karina's character in the film Vivre Sa Vie (1962).

Much like the look of Nana, Anna Karina's character in the film Vivre Sa Vie (1962).

An intertitle simply explains:

Strange and incredible thoughts were springing up in her mind.

while the book details:

...she took up a book, threw it away, took up another, laid that down, began to write a letter, then tore it up, and taking off her two rings she threw them on to the lid of the old-fashioned escritoire, which she used as a writing-table, and went to the piano. She played one of her favourite pieces, the great scene of the

apparition of the nuns in ‘Robert the Devil.' Opera music was the only kind which Marina ever played.

She played now as though the desires of the ghostly sinners had entered into her, only in greater strength. At the passage of the temptation she broke off, she could not go on. The internal fire within her was too strong for her, seemed to overwhelm her and choke her.

All this is masterfully captured in the body language of the "special interpretation by the diva", that make it clear that those "incredible thoughts" were a product of the "internal fire within her".

Let me return as Cecilia, let him love me under that name...

Right at that time, Marina happens to discover relics of Cecilia, and reads Cecilia's angry cry for revenge against the children of Count Emanuele (Count Caesar's father), because Count Emanuele and his mother imprisoned her, believing she was having an affair. The letter also claims that the reader will carry out the revenge while possessed by Cecilia's soul.

The contents of the letter in the film mostly match the novel. But the few missing pieces are critical to understanding subsequent events:

...whatever be your name, you who have found and are reading these words, recognise that within you dwells my own unhappy spirit.

...Remember the name of Renato, the red and blue uniform, the epaulettes, the gold lace and the white rose at the Doria's ball.

....Remember the vision which I had in this room two hours after midnight, the words of fire upon the walls, words in an unknown tongue...said that I should be born anew, that I should live again here between these walls, that here I should be avenged, that here I should again love Renato and be loved by him.

...Change names with me. Let me return as Cecilia, let him love me under that name... It is curious for me to be speaking to you as though you were not I.

Cecilia's words resonated with Marina, who had already felt the castle confining her passion, and Marina even imagines how Cecilia's fate unfolded: "She thought of seeing the creatures of the past surging from the shadows to tell her their drama" (the film's clever segue into an enactment of Cecilia's affair).

Cecilia's words resonated with Marina, who had already felt the castle confining her passion, and Marina even imagines how Cecilia's fate unfolded: "She thought of seeing the creatures of the past surging from the shadows to tell her their drama" (the film's clever segue into an enactment of Cecilia's affair).

The enactment shows how Count Emanuele's actions were driven by his mother's dominance, and Cecilia writes: "the Count Emanuele and his mother are killing me slowly". Indeed, the mother-son relationship is a recurring theme in the novel. In a parallel to Cecilia's fate, Marina becomes engaged to marry a man whose behavior is also driven by his mother's dominance. And although films tend to give a one-dimensional portrayal of Marina's uncle as consistently stern, the novel reveals that he grew fond of Marina, particularly because her passion for art was like that of his beloved mother:

In these discussions on art the Count displayed a most placable spirit; nay, a look of tenderness often came into his glance as Marina warmly defended her favourite painters ; the old man was reminded of his own mother, and listened in silence.

In addition, Silla goes on at length about his love for his mother, and he too is driven by his mother in spirit: it was her relationship with the Count that brought him to Malombra Bay.

You are the prisoner - you've always been the prisoner

With a force in a house possessing one of its inhabitants and driving that person to evil, a comparison between Malombra and the film The Shining (1980) is unavoidable.

The dead Grady insists on transferring his identity (the caretaker) to Jack, and later suggests violence is the caretaker's duty - just as Cecilia insists in her letter on transferring her spirit to the reader, and claims the reader will carry out her revenge. But while the question of whether the force is supernatural or psychological is left unresolved in the ambiguity of The Shining (when Jack talks to the dead Grady, Jack is facing a mirror), the force in the film Malombra is clearly psychological - as in the novel. The essay

The Italian Gothic and Fantastic: Encounters and Rewritings of Narrative Traditions

points out:

There are no ghosts in the story...no candles unexpectedly extinguish themselves, and there are no dungeons, no archetypal villain, no incest, and no child murder. In short, none of the melodramatic ingredients of the early gothic of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century are present.

But the same essay goes on to say of the novel:

The plot is imbued with a strong sense of predestination, as if what happens is a playing out of what has already been decreed. This suggests that there is no living human agency behind the events and so absolves any one individual of responsibility...In short, although the presence of the supernatural is limited, its actions determine the plot and its outcome, and relieve any one person of responsibility for the events that unfold.

That sense of predestination surrounded not just Marina, but also Silla: predestination was a core element in Silla's novel:

The subject of the book is as follows : — A young man...has a dream of extraordinary vividness, in which he imagines that he sees his own future set forth in the form of an allegory. The first part of the dream is realised by events. Fifteen years pass by. The second portion of the dream had predicted a violent attachment followed by some stupendous catastrophe. At the age of thirty-seven the hero is living as a married man in semi-seclusion from the world, to avoid the predicted disaster, when he falls a victim to an overpowering passion. The object of his

attachment is a lady of great intellectual and moral refinement...

In his reply to Marina's letter, Silla posits that preordained events are the work of deities:

In his reply to Marina's letter, Silla posits that preordained events are the work of deities:

That there are malignant spirits which make a sport of us is certain...Everything points to the belief that, as we exercise power over the beings inferior to ourselves, so we ourselves are subject, within certain limits, to the action of other beings of attributes more powerful than ours...

Prophetic dreams, presentiments, sudden artistic inspirations, sudden flashes of genius, blind impulses towards good or evil, inexplicable fits of high spirits and depression, the involuntary action of the memory, are

probably all controlled by superior beings, partly good, partly bad.

Such considerations, however...all fall to the ground if we deny God. He then added the hope that Cecilia was not an atheist, for in that event he would be compelled, with great regret, to break off the

correspondence.

And, when Silla returns to the castle, we learn of his long-held sense of foreboding:

...he thought of...his old sinister presentiment of one final, hopeless fall, of a horrible abyss waiting for him, he knew not at what turning-

point of his life, in which he would lose himself, body and soul, forever. He felt, without alarm, that he had reached the spot and had one foot over the yawning void.

What we see in this restoration is more strictly psychological than the novel, with no such sense of predestination present. The film places responsibility squarely in the mind of Marina - not a mind possessed or destined by the supernatural, but a mind acting from the delusions of its own creation - as her response to Cecilia's letter makes clear: "It's madness... ridiculous...". But the thought that the soul of Cecilia relived in her to exact revenge thrilled her mind already.