The maid is always the first to go

The film immediately distinguishes itself in its opening scene. A woman sneaks around in the kitchen, suitcase in hand, then peeks through a keyhole at another woman tending an infant. Who is this prowler, and what she's up to? Already the film has diverged from common practice, that of establishing the setting or action via intertitles (or at least visual clues), to deliver on the claim made in its stark title: Suspense.

The mystery woman seems unsure what to do, apparently affected by the image of the other woman and infant. After donning a hat as if to exit, she finally decides to write a note:

She then sneaks out more confidently: the note seems to have resolved her dilemma - and our suspense (momentarily) - while seamlessly establishing the setting, without breaking the action with a narrative intertitle (in fact, the film has no narrative intertitles).

She then sneaks out more confidently: the note seems to have resolved her dilemma - and our suspense (momentarily) - while seamlessly establishing the setting, without breaking the action with a narrative intertitle (in fact, the film has no narrative intertitles).

The servant is not listed as cast. Her role is simply to set off the action by leaving. Yet even that minor character was fleshed out with personal conflict, by suggesting she was torn between her self-interests urging her to leave, and something else that made leaving not easy, that compelled her to sneak out rather than inform the mistress directly. Was it a sense of duty, loyalty, empathy, pangs of conscience, or something else? A bonus takeout serving of suspense...In any case, she's surely watched Physician Of The Castle/A Narrow Escape (1908) and Cape Fear (1991), and thus knows that the maid is usually the first to go in these movies, so "Adios" mistress and baby.

"What's this all about? What's your angle?"

Just as the servant exits the screen, the real prowler enters it, spotting her departure as his opportunity. His arrival, coinciding with a phone call from the husband notifying Mother of his late return, sets the central conflict in motion - literally, completing the picture:

Trinity: Invader-Caller-Rescuer

Trinity: Invader-Caller-Rescuer

After the call, Mother discovers the servant's note. As expected, she immediately returns to the phone. But suprisingly she pauses, then sets the phone aside. Why? To avoid adding to her husband's burden? Besides, she didn't want to look like the wussy wife she saw in The Lonely Villa (1909).This was a new era: women could now vote in six states - twice as many as in 1909. Rather than emulate the domestic dependency of wives in Griffith films, she seeks to achieve some level of autonomy in her home. Who knows? Perhaps one day she'll also achieve autonomy outside the home, even make her own films - like that French woman she'd heard about...

Just then, her reverie is broken by the baby's coos. That serves as a reminder of her duty to protect: the price of autonomy is vigilance. She wisely locks down windows and doors. But, in her eagerness to return to cuddling the infant, she forgets the servant's key under the doormat that's mentioned in the note.

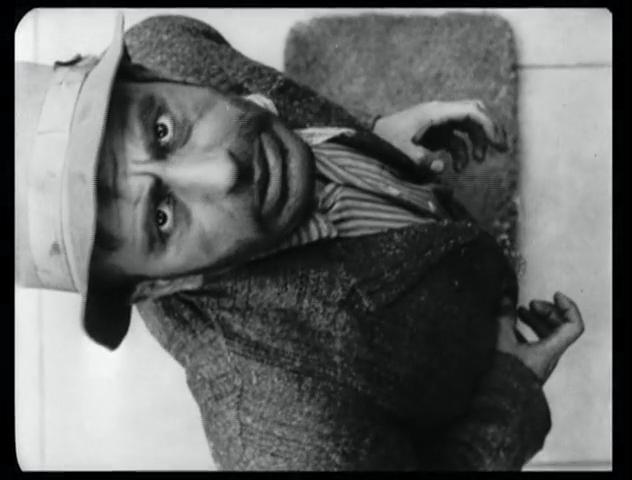

But the distraction of the infant doesn't dull her senses: something (a sound perhaps) leads her to go to the window and check below, where she spots the alternate title: The Face Downstairs.

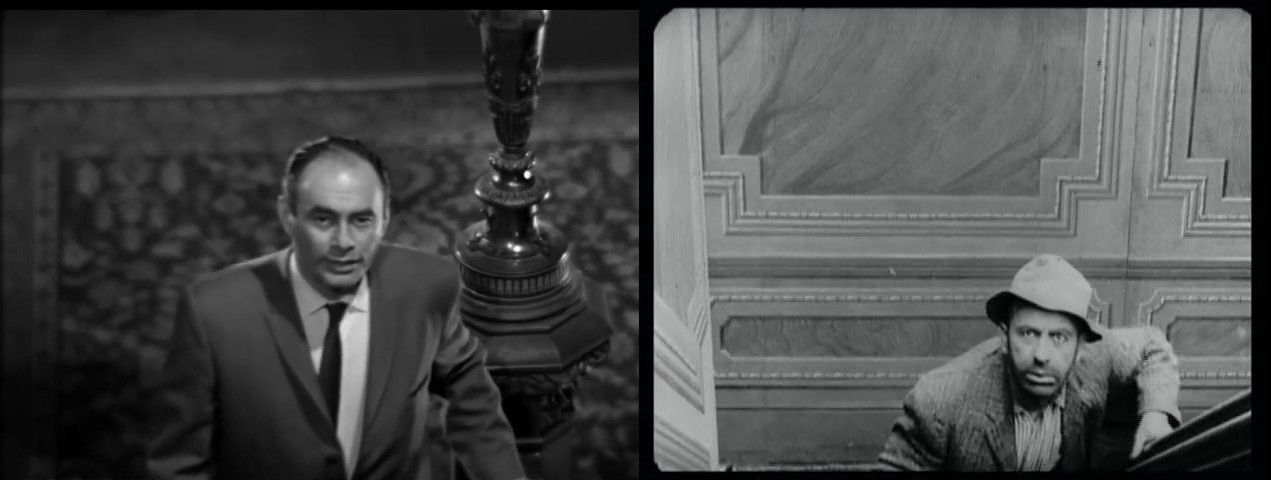

Make no mistake: to a lady trapped inside a pre-Chaplin film, a tramp at the door didn't bring chuckles, but instead signaled the threat of theft, kidnapping, murder, or even some kind of combo plate of these. But here the film's terror doesn't merely rely on a shared perception of the threat posed by the presence of a tramp. It personalizes the threat by zooming in to provide a closer look at the tramp's face than other films of that time gave. The tough life of a tramp is not likely to create an angelic appearance, so the forbidding look on the tramp's face could be viewed as a somber expresion of despair. But to ensure that the tramp's appearance is viewed as menacing, an additional effect is used: the tramp's face is rotated 90 degrees, adding even more unease to an already disturbing view - an effect later exploited in German expressonism and film noir. And taken to the max in Hitchcock's Notorious (1946), where even the suave charm of a Cary Grant can't overcome the resulting sinister appearance - as seen from the point of view of the woman who, after declaring "I hate low, underhanded people like policemen..." while partying with him, now realizes he is a policeman who has only befriended her so he can use her as a snitch, and asks him:

"What's this all about? What's your angle?"

Make no mistake: to a lady trapped inside a pre-Chaplin film, a tramp at the door didn't bring chuckles, but instead signaled the threat of theft, kidnapping, murder, or even some kind of combo plate of these. But here the film's terror doesn't merely rely on a shared perception of the threat posed by the presence of a tramp. It personalizes the threat by zooming in to provide a closer look at the tramp's face than other films of that time gave. The tough life of a tramp is not likely to create an angelic appearance, so the forbidding look on the tramp's face could be viewed as a somber expresion of despair. But to ensure that the tramp's appearance is viewed as menacing, an additional effect is used: the tramp's face is rotated 90 degrees, adding even more unease to an already disturbing view - an effect later exploited in German expressonism and film noir. And taken to the max in Hitchcock's Notorious (1946), where even the suave charm of a Cary Grant can't overcome the resulting sinister appearance - as seen from the point of view of the woman who, after declaring "I hate low, underhanded people like policemen..." while partying with him, now realizes he is a policeman who has only befriended her so he can use her as a snitch, and asks him:

"What's this all about? What's your angle?"

Alfred Hitchcock's Notorious (1946)

Alfred Hitchcock's Notorious (1946)

"Do what you can, with what you have, where you are"

Now Mother is facing a possible life-and-death struggle - tackling it alone is an option best avoided. Safety trumps autonomy, and she phones the husband without hesitation. And delaying the call until it was crucial actually could be a life-saver. Had she asked him earlier to return when there was no imminent threat, his pace would've been leisurely, yet he likely would be unreachable for a second call when the threat had elevated. But now he responds like a model rescuer: skipping the useless dramatics of the husband in The Lonely Villa and the brother in An Unseen Enemy (1912), he ditchs the phone the instant the line is cut, and is out in a flash - silently scolding himself for living in a remote location without a car.

Oh, and remember the key under the doormat? Of course you do. Everyone does - even tramps.

After cutting the phone line, the tramp silently praises himself for the resourcefulness he has shown today. "Believe you can and you're halfway there", he thinks - just like Teddy Roosevelt said. "Do what you can, with what you have, where you are".

Just then, his reverie is broken by the splendid sight of a plate of sandwiches. Unlike other one-dimensional film tramps, this tramp is shown from multiple views. The menacing threat shown earlier was Mother's view. This view of an invading tramp whose primary goal is to fill his empty belly is in direct contrast with that of the invited tramp in Tracked by Bloodhounds (1904), who refused the food offered him, preferring to loot and kill.

Belly full, he is ready to continue his exploration. But he must be prepared for the danger faced by anyone venturing into the unknown. He realized he was following the path of another uninvited brave soul exploring a house - the detective Arbogast in Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960):

Yet he had no desire to follow that path to its end, and meet with Mother:

So, clutching the kitchen knife for protection, he cautiously moves on - just like Teddy Roosevelt said:

"Do what you can, with what you have, where you are".

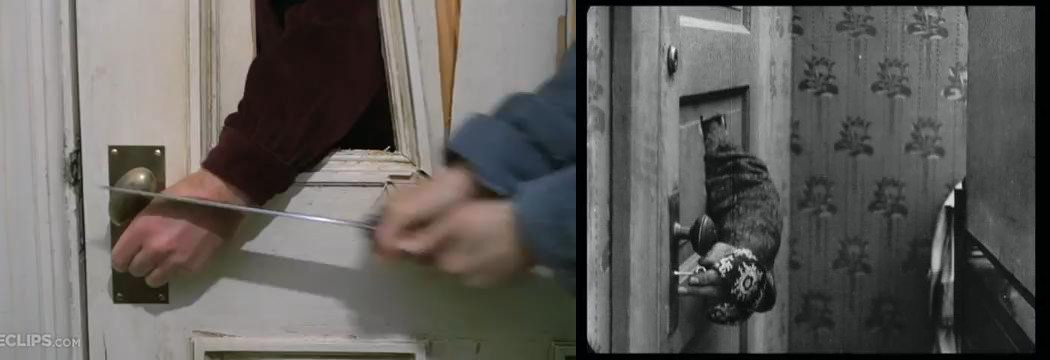

Teddy's can-do spirit motivated him, but he learned the how-to from watching the movies. Watching The Shining (1980) taught him that making a showy entrance may require you to give Mother a hand. Better to be smooth, and wear protection, in case you encounter Mother - even if you've got an axe to grind, she's quite handy with a kitchen knife.