A Chopical Paradise?

Travel articles proclaim that the land route between the Sarawak towns of Miri and Lawas (along the Pan-Borneo Highway) is heaven for passport

stamp collectors.

But even the most hardcore collector is likely to feel its hellish side at some point in passing through the eight

international checkpoints along the way. That means eight times queueing up. That means eight times struggling to appear relaxed, as powerful

enforcers of arcane laws either keenly eyeball you with suspicion, or stamp you with a wooden gaze that momentarily sucks you into the vacuum

of their dreary existence. That also means eight times laboriously checking your passport to ensure that you will not be held responsible for

their bleary-eyed mistakes.

Travel articles proclaim that the land route between the Sarawak towns of Miri and Lawas (along the Pan-Borneo Highway) is heaven for passport

stamp collectors.

But even the most hardcore collector is likely to feel its hellish side at some point in passing through the eight

international checkpoints along the way. That means eight times queueing up. That means eight times struggling to appear relaxed, as powerful

enforcers of arcane laws either keenly eyeball you with suspicion, or stamp you with a wooden gaze that momentarily sucks you into the vacuum

of their dreary existence. That also means eight times laboriously checking your passport to ensure that you will not be held responsible for

their bleary-eyed mistakes.

Welcome to Heaven

While some citizens may rejoice at how this exercise in sovereignty sanctifies the nation from alien sin, visitors are likely to question the pragmatism of a route, within a single state of a nation, forcing overland (but not flight) travellers through international checkpoints.

But when I lamented the absurdity of it all while conversing with an immigration agent, he held that it is essentially a vestige of colonialism. Still, he had no clear explanation for its continued existence over 30 years after Brunei's independence, and over 50 years after the federation of the independent territories of the Malayan peninsula, Sabah, and Sarawak.

"You fucked up: you trusted us!"

The most notable anomaly of Brunei borders is that the small country consists of two disconnected areas, with Sarawak's Limbang district separating the two areas. If the two areas were not disconnected, then half of the border crossings disappear. So it is reasonable to seek out the origin of the split.

Although the historical record of early Borneo is scant, it is alleged that the Bruneian Empire, at its peak in the 15th century,

controlled most of Borneo. But its decline began in the 19th century, when the Brunei sultan faced a rebellion in Sarawak. James Brooke,

an adventurer and former officer in the private army of the British East India Company assisted in crushing the rebellion. In 1842, the sultan

ceded complete sovereignty of Sarawak to Brooke, and granted him the title "Rajah of Sarawak" as reward for his counter-insurgency work.

Although the historical record of early Borneo is scant, it is alleged that the Bruneian Empire, at its peak in the 15th century,

controlled most of Borneo. But its decline began in the 19th century, when the Brunei sultan faced a rebellion in Sarawak. James Brooke,

an adventurer and former officer in the private army of the British East India Company assisted in crushing the rebellion. In 1842, the sultan

ceded complete sovereignty of Sarawak to Brooke, and granted him the title "Rajah of Sarawak" as reward for his counter-insurgency work.

Brooke appointed his nephew, Charles Brooke, as his successor in 1885. When the younger Brooke continued to seize more land, the sultan negotiated a treaty with Britain for protection against his former protector. But the Brunei side apparently neglected to read the treaty's fine print, which only ensured protection against "foreign" intervention. So when Charles Brooke seized Limbang for Sarawak in 1890, the sultan's new protector did nothing to protect Brunei from its former protector, despite the treaty, because Sarawak was not considered "foreign". Brunei was left split into two, yet remained under British control until 1984.

So it seems somewhat inaccurate to simply blame colonialism for Brunei's bifurcation, when it was perhaps more the result of the Brunei sultans' consistently poor choice of alliances. Although Brunei still seems to maintain an unresolved claim on Limbang (thus making Brunei's checkpoint restrictions even more absurd, since the claim implies that travel between Brunei and Limbang is not international), the Brunei's dynasty of sultans clearly fared better than some other autocrats who also cut deals with the devil.

Borderland Blues

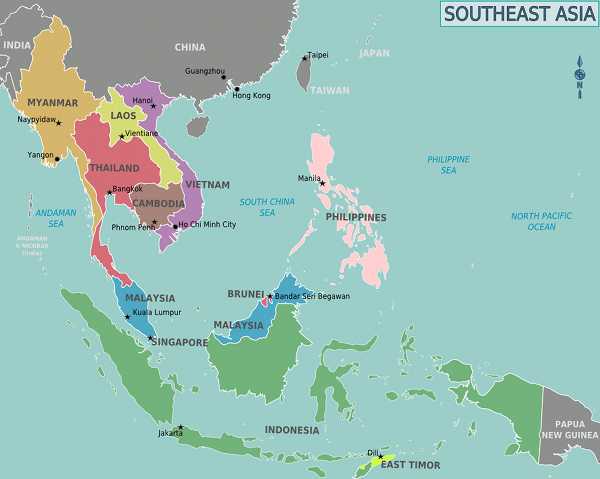

But, as mentioned, Limbang splitting Brunei is only half the problem. The only way to avoid the remaining four checkpoints would be a direct overland route that bypassed Brunei. But, as the map below shows, an inland bypass route would have to cut through forests and mountains - a formidable challenge to economic and environmental resources.

But even if history and geography do conspire to force all overland travel between Miri and Lawas through Brunei, shouldn't travel on that stretch of the Pan-Borneo Highway be seamless by now? But instead, the news reports:

- 2011 Christmas: Call to open M'sian-Brunei border checkpoints 24 hours

-

- On Christmas eve, traffic congestion along the Limbang- Brunei-Lawas immigration checkpoints forces commuters to spend the night in their vehicles after the counters closed for the day.

- Rush caused traffic standstills up to 5km long at the border checkpoints.

- 2014 Chinese New Year: Massive congestion at Sarawak-Brunei checkpoints spoils festive mood

-

- Congestion stretched over several kilometres from the Brunei side and lasted for hours.

- The immigration checkpoint on the Miri side had 22 lanes, but only 4 were open.

- 2016 New Year's Day: Long queues at checkpoint irk travellers

After decades of rapid development in their economies, residents of Malaysia and Brunei (along with travellers and commercial traffic) continue to endure a mutual border that is inadequately staffed, frequently congested, and completely blockaded 25% of the day when the border shuts down (midnight to 6AM).

Indefinite delay, severe restriction of movement, part-time imprisonment: all just daily routine in the borderland. But what happens in an emergency?

Adding insanity to injury

Apparently, medical emergencies and ambulances are not exempt from checkpoint restrictions. Recently,

the Borneo Post

explained why Lawas residents needing medical care that is not available at the Lawas hospital prefer to go to Sabah's Kota Kinabalu

Hospital (KKH) rather than Sarawak's Miri Hospital:

...patients in Lawas preferred to be sent to KKH because it took only two hours for them to reach the hospital.

For them to travel to Miri, it takes about five hours where they have to go through two immigration checkpoints which operate only

certain hours.

Once the checkpoints are closed after midnight, the situation could be critical for emergency and critical cases because Lawas Hospital

has no specialists to handle such cases.

It is thus more convenient for patients from Lawas and even Limbang (which is 45 minutes from Lawas) to seek treatment at Kota Kinabalu

Hospital than in Miri Hospital.

But this explanation is unclear, because:

-

As is well-known (and as previously published in the Borneo Post ), the journey from Lawas to Miri passes through eight checkpoints, not two.

-

It fails to mention that any road journey from Lawas to Kota Kinabalu also must pass through two checkpoints - at the Sarawak-Sabah state border. These checkpoints also have the same operation hours as the Malaysia-Brunei checkpoints (closed midnight to 6AM).

So it is not clear how access to Kota Kinabalu hospital effects the fundamental issue: for six hours each day, the 40,000 residents of Lawas district are held captive under barbed wire, with no access to major medical care.

-

The journey from Limbang to Miri and the journey from Limbang to Kota Kinabalu both pass through four Malaysia-Brunei checkpoints. The Limbang to Kota Kinabalu journey, however, must also pass through the two additional checkpoints at the Sarawak-Sabah state border. It's completely unclear why Limbang residents would view Kota Kinabalu Hospital as more convenient than Miri Hospital.

It is clear, however, as in the Lawas case, the 48,000 residents of Limbang district are held captive with no accesss to major medical care for a significant portion of each day.

This January 2013 photo shows a rented row of new shophouses, to be renovated to temporarily house Lawas Hospital, to facilitate the construction of a new hospital. Although the new hospital was proposed by the prime minister in 2006, and approved by Parliament in 2008, it was reported in April 2016 that work on the new hospital had not begun, and the project is not scheduled for completion until 2019, "after prolonged delay caused by many factors" - that were never specified.

Updates: The Lawas Hospital project

- 2023-03: ‘No more extensions, expedite Lawas Hospital construction’

The state government said that after previously giving flexibility to the contractor during the Covid-19 pandemic and movement restrictions, as well as an extended period for the hospital’s construction, the state government will not allow any extension for the completion date of the construction of the Lawas Hospital and will ensure it is completed by Dec 2024.

The construction of the Lawas Hospital started on June 30, 2020 and was initially expected to be complete by December 2023, before the deadline was extended to Dec 11, 2024. It was initially scheduled to start construction in 2011 and slated for completion in 2016.

Full story- 2019-12: Lawas Hospital construction project launched

-

Construction work starts in February, to be completed by 2023 - seven years later than its original scheduled completion date. Bandar Kuching MP Dr Kelvin Yii said: “Hopefully, it will start as soon as possible, but please monitor (the Lawas Hospital project) because based on history, we know ‘pecah tanah’ (groundbreaking) means nothing”. Agnes Padan, a rural health care advocate who previously sued the Lawas district hospital for negligence over the death of her mother, has asked what happened to the 2012 allocation for construction work at the hospital, and said as of December 14, she saw no signs of construction of the hospital starting anytime soon, even though Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad promised to start construction in November.

Full story - 2018-09: Film highlights the human cost of the wretched state of healthcare in rural areas dependent on Lawas Hospital

-

"Kam Agong was an ordinary mum from Long Semadoh in rural Sarawak. In 2002, she bled to death in her village a month after giving birth by C-section at Lawas District Hospital, the nearest maternity facility, five hours away. Her daughter and son-in-law sued the hospital for medical negligence and won."

Full storySixteen years after Kam Agong's death her daughter, Agnes Padan, continues to bring attention to the issue with a heartrending 30-minute film The Story of Kam Agong, which can be viewed on YouTube.

"10 years have passed since we won the case. But until today, nothing has changed. The Long Semado Clinic and Lawas Hospital are still the same as it was."

- 2018-08: New government declares Lawas Hospital project one of the previous government's 'sick' projects

- The new Works minister acknowledged:

"The delay in building the hospital has caused much hardship to the people and even loss of loved ones. Patients in critical conditions have to be sent to Kota Kinabalu or to Miri for treatment. Some of the people in Lawas do not have passports and cannot be sent by road to Miri as that involves crossing Brunei...Needless to say, some patients who could have been saved died as a result of this problem of lack of healthcare."

Full story

ASEAN "Connectivity"?

This tale of obstruction, imprisonment, and disregard for public health needs is disturbing. But, in the broader context, it also does not

bode well for plans for regional integration, as described on the ASEAN webpage:

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, was established on 8 August 1967 in Bangkok, Thailand, with the signing of the

ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) by the Founding Fathers of ASEAN, namely Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.

Brunei Darussalam then joined on 7 January 1984, Viet Nam on 28 July 1995, Lao PDR and Myanmar on 23 July 1997, and Cambodia on

30 April 1999, making up what is today the ten Member States of ASEAN.

AIMS AND PURPOSES

As set out in the ASEAN Declaration, the aims and purposes of ASEAN are:

... the improvement of their transportation and communications facilities and the raising of the living standards of their

peoples...

Fundamental to the ASEAN vision is establishment of an EU-style ASEAN community, "that will bring peoples, goods, services and capital closer together", and as an ASEAN Master plan points out:

An enhanced ASEAN Connectivity is essential to achieve the ASEAN Community.The Master Plan also makes clear:

Physical connectivity per se cannot guarantee seamless movement of goods and people across countries. Inefficient and lengthy cross-border procedures [emphasis added], which add unnecessary friction and costs to transport, are serious challenges that need to be addressed...

...Hence, cross-border facilitation and management is an essential component of enhanced ASEAN connectivity.

Clearly, in regards to "the improvement of their transportation and communications facilities and the raising of the living standards of their peoples", Brunei-Malaysia border management has not been an ASEAN success story. And if the political leaders that devised and manage ASEAN (and forced it on the region without any input whatsoever from "their peoples") have any real concern for its peoples, then the Brunei-Malaysia border fiasco should worry them. Why? Because that border may be the ASEAN land border that is least problematic, and most free of tension and hostility.

Brunei and Malaysia share strong political, cultural, historical, and economic ties. Politically, they are the only ASEAN members that declare Islam as the official national religion. Although Sarawak has no official state religion (Sarawak is Malaysia's only Muslim-minority state), its historical connection with Brunei has left cultural ties. The two nations' shared interests in maintaining petroleum exports has led to economic cooperation.

Other land borders present much greater difficulties.

ASEAN's borderline insanity

Source: Wikimedia

- Cambodia-Laos:

-

A persistent claim in Cambodia's political discourse is that the country has lost considerable territory to its neighbours. Thus, all border issues are sensitive.

Because Laos is viewed as less of a threat than the economically and miltarily stronger neighbors, Thailand and Vietnam, border relations with Laos have been characterized by relatively minor but sustained tensions, amid a long-standing unresolved border dispute.

- Cambodia-Thailand:

-

Long-standing border dispute that has resulted in periodic military clashes. In 2011 Thailand admitted to using banned cluster bombs during clashes, placing thousands of villagers in the border area at future risk of death or serious injury because of unexploded bombs near their homes.

- Cambodia-Vietnam:

-

Even though over 80 percent of the 1137-km borderline has been jointly demarcated through negotiations ( as of the end of 2015 ), territorial disputes with Vietnam remain a political hotspot in Cambodia - reportedly stoked by the opportunistic political actors. Cambodia's long history of invasions from Vietnam, and periods under the control of Vietnam, have contributed to deeply-rooted anti-Vietnamese sentiments. The most recent invasion resulted in war from 1977-1991 and Vietnamese ousting the Khmer Rouge, and installing the current governing party - that is viewed as too close to Vietnam (or even a Vietnamese puppet regime). Consequently, anti-Vietnamese sentiment has served as a tool of the opposition, as well as a preemptive defense mechanism of the ruling party. Hence, one author calls the stance that flags the Vietnamese as a territorial threat "a central pivot of Cambodian politics").

- Indonesia-Malaysia:

-

Although the border's length is over 2000 km, there is only one official crossing. That makes people or goods crossing at all other points along the lengthy border "illegal immigrants", and "contraband" (i.e.,the reality of normal human activity is rendered illegal by unrealistic conditions of legality). The "illegal immigration" issue is a hotspot in Malaysia politics, with the government at one point declaring "...in Malaysia illegal immigrants are enemy No. 2”, with drugs No. 1 (No indication given on where terror attacks and other violent crime stood in this ranking, but clearly the state prefers enemies to be unarmed and helpless).

- Laos-Myanmar:

-

The 238-km Lao border with Myanmar is defined by the Mekong River, which flows from southern China to the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam. In May 2015 Myanmar and Laos opened their first "friendship" bridge across the Mekong River, a route previously only shuttled by ferry. Relations have been cooperative, but bilateral trade is low - their economies, along with Cambodia's, are ASEAN's weakest.

- Laos-Thailand:

-

After a border dispute resulted in military clashes in 1984 and 1987, the two countries set up a joint border committee in 1996 to demarcate the 702-km land boundary, but progress has been slow. Although 96% complete in 2012, it remained unresolved in July 2016 .

- Laos-Vietnam:

-

In descriptions of the Laos-Vietnam relationship, the word "special" keeps coming up, from both the Laos and Vietnam side (Thankfully, this "special relationship" has not produced the global disaster spawned by a more well-known "special relationship").

But following the French and US wars against Vietnam, despite expressions of solidarity between the ideologically-linked ruling parties, there were few resources available for mutual development. Now, however, Vietnam's investment in Laos is reported to be second only to China's. This may be the only ASEAN border relationship that can rival the Brunei-Malaysia border relationship in strength of political, historical, and economic ties.

- Malaysia-Thailand:

-

For over ten years, two of the four provinces that sit on the Thailand side of the border (Narathiwat and Yala) have been the site of an insurgency that has left over 6300 people dead (and sometimes spreads into a third border province, Songkla) - and shows no signs of cooling down.

- Myanmar-Thailand:

-

Decades of internal conflict in Myanmar have resulted in this 2401-km border hosting "over 120,000 displaced persons in nine UNHCR-run camps, and an estimated 500,000 to 1 million registered and undocumented migrants ", according to the World Health Organization.

In addition, this border, part of the infamous Golden Triangle, traditionally hosts sites for refining opium into heroin. But as the heroin trade has shifted to Afghanistan, border trade has shifted to the booming methamphetamine biz.

Clearly, by comparison, resolving Brunei-Malaysia border issues should be like a walk in the park on a sunny afternoon. The Brunei-Malaysia border should be a model for other ASEAN member states, showcasing the realization of the declared aspirations of ASEAN. Instead, the rulers make little or no progress towards realizing the goals they've set, while the people who have already implemented the goal of "seamless movement of goods and people across countries" are jailed as "illegal immigrants", and "smugglers".

Isn't it time to push the reset button?