Bold Bank Robbery Gives Back

Bold Bank Robbery is not usually cited as a significant or influential film. Yet it contains a number of elements that were not

commonly found in films at that time, but later were widely used:

- "Bookends" as a framing device

- Birth of the "Gentleman Thief" film

- "Heist film" elements

- Towards the visual style of expressionism and noir

"Bookends" as a framing device

Films in the early era rarely presented a sense of structure to the viewer. Action films, in particular, tended to immediately reveal

the main conflict, with little or no introduction to characters or setting. From there the films then rush (usually via a chase) towards

the conflict's resolution, never looking back - forming an "extended incident" with a single cause and an extended effect, rather than a

sequence of causes and effects. The predecessors of Bold Bank Robbery - A Daring Daylight Burglary,

Desperate Poaching Affray, and The Great Train Robbery - all followed the style of the extended incident.

Bold Bank Robbery was exceptional in establishing its characters and their milieu in the opening shot, and then again in an analogous

closing shot - bookends - that show a change that reveals the story's message.

The Great Train Robbery, popularized the emblematic shot, a close or medium shot placed at the beginning

or end, as explained in

The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960

:

Following the lead of The Great Train Robbery, quite a number of films of 1903-5 begin or end with medium shots of the

characters; these may introduce the characters before the action proper begins...The Bold Bank Robbery (1904, Lubin)

begins similarly with the three smiling robbers in evening dress and ends with a cut-in within a prison scene; now the three are in

convicts' stripes, frowning. Here the close shots structure the beginning and ending, providing a 'crime doesn't pay' moral for the

whole.

For these are Jolly GoodFellas

For these are Jolly GoodFellas

The Thrill is Gone

The Thrill is Gone

In the surviving popular films of the era such shots

are typically outside the film's narrative. In fact, some sources claim this as a defining quality of emblematic shots, as in

The Transformation of Cinema, 1907-1915, Volume 2, Part 2

:

Today's film theorists describe them as nondiegetic or emblematic shots: they are related to the film and comment on it,

but are definitely not part of the events of the narrative.

The famous emblematic shot of The Great Train Robbery is abruptly outside the narrative: the Edison catalog suggested that the shot

could be used at the beginning or the end! Its actual purpose is described in

Laughing Gas: The Close-up and Racial Spectacle

[quoting The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde]:

A discontinuous “attraction” autonomous from the film narrative, this “primitive” use of the close-up does not plunge toward the

bandit’s face in some last-ditch effort at characterization or audience identification, but rather provides an exhibitionist display

designed to startle or surprise the audience; it is, in short, a remnant from the cinema of attractions where

“[t]heatrical display dominates over narrative absorption, emphasizing the direction stimulation of shock or surprise at the expense

of unfolding a story.”

But the emblematic shots of Bold Bank Robbery, definitely are part of the events of the narrative,

as detailed in the Lubin summary of the film:

Scene 1 - The opening of the picture shows the robbers in gentlemen attire. They are short of money and decide to rob a bank.

Scene 2 - The robbers are seated in one of the most fashionable cafes of the city where they lay out the plan for the Bold Bank Robbery.

...

Scene 30 - In the final scene, the three convicts are seen discussing the failure of their Bold Bank Robbery and putting the blame

one to another.

In that respect, the emblematic shots of Bold Bank Robbery are innovative - as pointed out in

Life to Those Shadows

:

But at the same time more far-sighted spirits began to forge more consistent links between the emblematic shot and the main body of the

narrative. One of the innovators was a notorious 'plagiarist', Siegmund Lubin. In his Bold Bank Robbery (1904),

the initial presentation of the three gentlemen-crooks is made by a portrait shot which, although it is not matched with the succeeding

action, is shot on the same set with the same characters dressed in the same costumes and in the same positions; they are simply posing

for the cameraman. The same is true of the final picture, in which the three pose once again, but this time in their convict's uniforms.

Using bookends as a framing device is still popular - and still effective. For example, American Gangster (2007), begins with the

protagonist in the nighttime streets calmly setting a victim aflame, then shooting him, while standing at his boss' left side in a dark

portrait of power over life and death.

It ends with the protagonist now in the daytime streets, this time with the former cop that sent him to jail for 15 years. While standing at

the ex-cop's left side, the ex-cop saves him twice: first from the threat of young hoods, then from getting run down while crossing the street,

where the movie ends in freeze-frame. The clear message is that the protagonist has been completely broken and is dependent on the ex-cop who

now holds power over his life and death.

Bookends: Opening of American Gangster (2007)

Bookends: Opening of American Gangster (2007)

Bookends: Closing of American Gangster (2007)

Bookends: Closing of American Gangster (2007)

On a side note, "race" is a central element to the story of American Gangster, so if the racial overtones of the protagonist's

subordination to the ex-cop seem disturbing (Denzel Washington, 20-time winner of NAACP Image Awards, was not nominated for this role), just relax - that's part of the message too. Because this film was made by Ridley Scott, who

upholds the legacy passed down by D.W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation in such films as Exodus: Gods and Kings

(aka

Mohammad so-and-so

), The

(

white-washed

) Martian, and the movie that a

NY Times review said

"reeks of glumly staged racism", Black Hawk Down.

To summarize, Bold Bank Robbery used the emblematic shot as no other film had, to:

- Introduce the characters and show their traits (close friends, living the high life)

- Conclude the narrative with a message

- Structure the film, with analogous opening and closing shots

But Bold Bank Robbery blazed a new path not only in showing the criminals as characters (rather than faceless fiends, always seen

from a distance), but also in presenting a criminal look not seen before: jolly good fellows who are "robbers in gentlemen attire".

Birth of the "Gentleman Thief" film

The film could also have been titled Bold Bank Robbers, because the story is not only about the robbery, but also about the robbers.

The film humanizes the outlaws by providing them with faces and showing their lifestyle and camaraderie (in marked contrast to

The Great Train Robbery, which shows no faces until the famous final scene of the bandit firing at the camera.). And, in so doing, a new character type is introduced to cinema: the gentleman thief.

The Lubin summary of the film makes it clear that the

robbers are not like the skulking ruthless mugs featured in A Daring Daylight Burglary, The Pickpocket, and

Tracked by Bloodhounds:

Scene 1 - The opening of the picture shows the robbers in gentlemen attire...

Scene 2 - The robbers are seated in one of the most fashionable cafes of the city...

Scene 5 - The carriage has arrived at an apartment house in one of the finest resident sections of the city where the robbers live...

Scene 7 - One of the finest Packard automobiles has been ordered to bring the robbers to their destination.

The gentleman thief may have been new to cinema, but from 1898 to 1909 A.J. Raffles

was literature's second most popular fictional character, surpassed only by Sherlock Holmes.

As described in Raffles: The Gentleman Thief,

Raffles "mingles with the upper class but is, in fact, a jewel thief-a master cracksman who makes his living by stealing from his wealthy

acquaintances". He is, by design, an inversion of Sherlock Holmes.

Raffles became a Broadway stage hit in a production that premiered in October 1903, with 168 performances before closing in March 1904.

Raffles' first official screen appearance was over a year after Bold Bank Robbery, in the 1905

Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman.

Numerous films followed, and Raffles even had a 1977 British TV series. The gentleman thief has become an enduring screen character,

perhaps even indirectly influencing real-life thieves, like the notoriously less than gentle man James Burke, aka "Jimmy the Gent",

who also made it to the screen as the model for the character "Jimmy 'The Gent' Conway", played by Robert de Niro.

in GoodFellas (1990).

"Jimmy The Gent" Burke, and Robert de Niro as "Jimmy The Gent" Conway in GoodFellas

"Jimmy The Gent" Burke, and Robert de Niro as "Jimmy The Gent" Conway in GoodFellas

In fact, the potential lure of the heroic image of the gentleman thief has always been of concern. Arthur Conan Doyle, author of Sherlock Holmes

stories, said of the A.J. Raffles stories:

I think there are few finer examples of short-story writing in our language than these, though I confess I think they are rather

dangerous in their suggestion...You must not make the criminal a hero.

Apparently, the publisher of Raffles stories was in complete agreement with Doyle: the Raffles stories were published under the dire title

In The Chains Of Crime, with an equally dire illustration. Despite that, the series was still denounced by moralists as "new,

ingenious, artistic, but most reprehensible".

In that light, it certainly seems at least a possibility that the standard interpretation of the ending of Bold Bank Robbery,

as the film's message of "crime does not pay", may be somewhat naive. Another possibility is that the film had no more message than the

A.J. Raffles stories, and only sought to create an artistic story that capitalized on the twin vogues for the crime film and the

gentleman thief story. In that respect, the ending can be seen as a parallel to the In The Chains Of Crime illustration:

merely an attempt to avoid the wrath of the moralists.

In that light, it certainly seems at least a possibility that the standard interpretation of the ending of Bold Bank Robbery,

as the film's message of "crime does not pay", may be somewhat naive. Another possibility is that the film had no more message than the

A.J. Raffles stories, and only sought to create an artistic story that capitalized on the twin vogues for the crime film and the

gentleman thief story. In that respect, the ending can be seen as a parallel to the In The Chains Of Crime illustration:

merely an attempt to avoid the wrath of the moralists.

In The Chain Gang Of Crime

In The Chain Gang Of Crime

"Heist film" elements

The capers of the gentleman thief are bold, and executed with precision. As the character of the gentleman thief began to shift to the

background, while the cleverness and precise execution of his capers received more attention, a new genre developed: sometimes

called the big caper film, but more often known as the heist film.

Various definitions abound, but the most concise and apt is found in

The BFI Companion to Crime

which specifies them as films:

...in which professional crooks plan and execute a clever, daring but (the censors insisted) ultimately unsuccessful robbery.

Often the thieves fall out, or make one fatal error that leads to their arrest.

The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Rififi (1955), The Killing (1956), and Bob Le Flambeur (1956) established

the core traits of the heist film.

While some film critics list The Great Train Robbery as the first heist film, the one-reel format of that era did not provide

sufficient time for a film to detail characterization and heist planning in the way that has come to be associated with heist films.

So it may be more suitable to view these films as related to the heist film, rather than categorizing them as heist films themselves.

Then, under those terms, it can be shown that Bold Bank Robbery is the closer relative to the heist film:

- Characterization

-

The heist film gang may or may not be gentleman thieves, but they always must be characters viewers sympathize with.

But The Great Train Robbery clearly could not be accused of portraying criminals sympathetically. They are shown

brutally beating a man before tossing the body off the train, then robbing, shooting, and terrorizing passengers. When

all the robbers are finally killed, viewers shed no tears. But Bold Bank Robbery does not distance viewers from

the robbers in that way. They are first shown in closeup as jolly fellows. They sit well-mannered in a fashionable cafe,

where they tip the staff. They robbed the bank only, not people. Although carjacking requires the use or threat of violent force,

that is not shown. So, as with the heist film, viewers can easily find themselves rooting for the thieves.

- Planning

- Bold Bank Robbery includes one brief scene of heist planning, while The Great Train Robbery omits the

planning completely (although the more complex nature of its robbery implied skillful planning).

- Cleverness

- In a proper heist film, viewers must always be awed by the thieves' resourcefulness - either high tech or clever use of low tech.

No points for The Great Train Robbery here: though execution is smooth, it's all done with brute force.

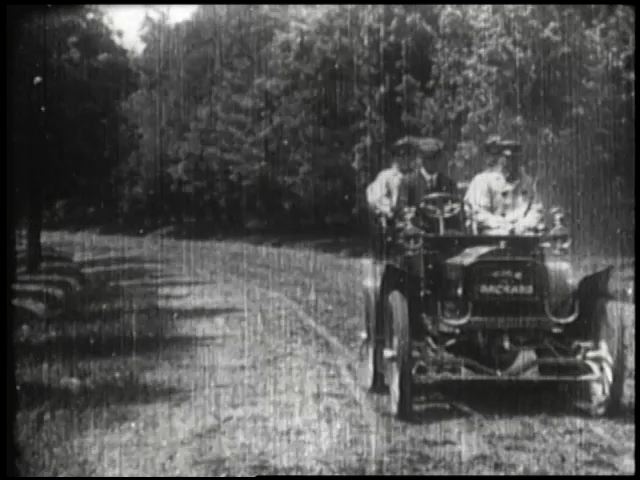

But Bold Bank Robbery showcased an impressive innovation that modern film critics seem to have overlooked:

possibly the earliest known film use of the "getaway car"! While the entire Internet seems to agree that the earliest known

historic use of a getaway car in a bank robbery was in the 1911 Bonnot Gang robbery, Wikipedia cites one news report from 1909.

So if the 1904 use of the getaway car in Bold Bank Robbery was not reenacting an earlier (but now unknown) historic use,

then the film must have either invented the idea or taken it from another (now unknown) bank robbery film or fictional story.

In any case, viewers of the day most likely were indeed awed, especially since any cars were uncommon then - and this one was a

Packard luxury car, starting price about $70,000 in 2016 dollars. Viewers then knew that in a vehicle chase, the cops

would've been smoked like fag butt.

Possibly the first getaway car, rolling in loot

Possibly the first getaway car, rolling in loot

In hot pursuit: police wagon, powered by two horses

In hot pursuit: police wagon, powered by two horses

Towards the visual style of expressionism and noir

Looking at parallel scenes in Bold Bank Robbery and The Great Train Robbery, the unusual visual

composition of Bold Bank Robbery is striking. While The Great Train Robbery has a dull, flat, conventional look of straight

lines and right angles, Bold Bank Robbery seems to be experimenting with shades of light and dark, and with diagonal lines cutting the

screen:

Scene 10: Bank guard's angular stance, and the pattern of teller cages

Scene 10: Bank guard's angular stance, and the pattern of teller cages

Scene 11: robbers search for the vault (missing from YouTube video)

Scene 11: robbers search for the vault (missing from YouTube video)

Scene 12: Searchlight on wall pattern

Scene 12: Searchlight on wall pattern

Scene 17: The sloping road

Scene 17: The sloping road

Bold angles together with the play of light were part of the experimentation that marked German Expressionist films, like

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Years later, film noir added the visual techniques of German Expressionist films to crime stories, to tell disturbing tales

of life out of balance, as in I Wake Up Screaming (1941).

I Wake Up Screaming (1941)

I Wake Up Screaming (1941)

Conclusion

With so many early films now lost, it's rather meaningless to tout "the first..." as a film's accomplishment. But, from the films that have

survived, the achievements of Bold Bank Robbery are tough to match, boasting the early use of:

- The emblematic shot within the narrative

- Characterization of the criminal as antihero

- Bookends as a framing device

- The gentleman thief protagonist

- The getaway car in a robbery

- Proto-noir visual elements

Clearly, Bold Bank Robbery got an early start towards a highly influential direction in filmmaking. Which leads to an obvious question:

why is Bold Bank Robbery often dismissed or disregarded in film history?